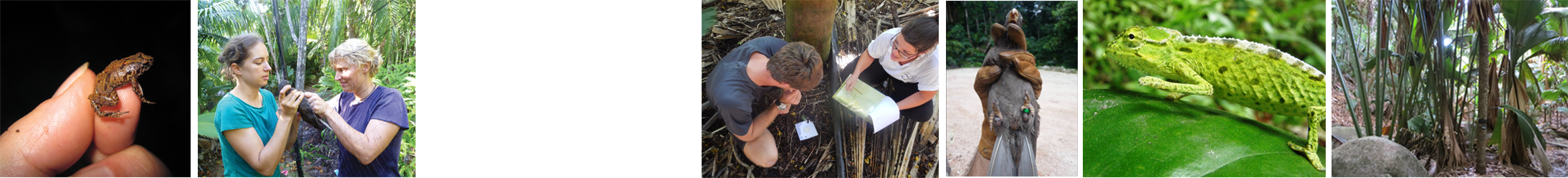

The sooglossid frogs are a group of endemic frogs that were, until recently, known only from the Seychelles islands of Mahé and Silhouette. The Seychelles group is atypical for islands in having several species of amphibian, which usually cannot cross saltwater barriers to reach oceanic islands. The reason for Seychelles’ unique amphibian diversity is that most the archipelago’s inner islands are not volcanic, but granitic, and therefore continental in origin. Amphibian species therefore did not have to cross oceans to reach these islands but were already present when the Seychelles split from Madagascar and the Indian subcontinent, and then continued on their unique evolutionary trajectory, eventually resulting in the astonishing endemic amphibian hotspot we see today. Several Seychelles amphibian and reptile families are endemic to the country and contain several species. One example is the family of Seychelles sooglossid frogs, famous for being some of the smallest frogs in the world, which, until 2009, contained four species (Sooglossus thomasseti, Sooglossus sechellensis, Sechellophryne gardineri and Sechellophryne pipilodryas) on only two islands.

Then, in 2009 a new sooglossid frog population was discovered at the Vallée de Mai. This new ‘Praslin sooglossid’, closely resembles the existing species Sooglossus sechellensis, but the new frog is a different in its size and calls. The calls are an important feature as they are thought to be unique to each species. This new discovery is exciting as it represents either a significant range expansion of an existing sooglossid species, or potentially, an undescribed species - research is underway to determine which!

All of the sooglossid frogs found in the Seychelles are unique and distinctive. Not only does each species have a different call, they have a very different reproductive cycle to many other frogs. Rather than laying eggs in a body of water the sooglossids are fully land-based with no water-born tadpole stage. After the female lays her eggs, one or both of the parents guard the eggs until they hatch. For some sooglossus species, once the eggs have developed and hatched into tadpoles, they are carried by the female on her back until their complete transition into tiny froglets. Eggs of other sooglossid frog species hatch directly into small froglets.

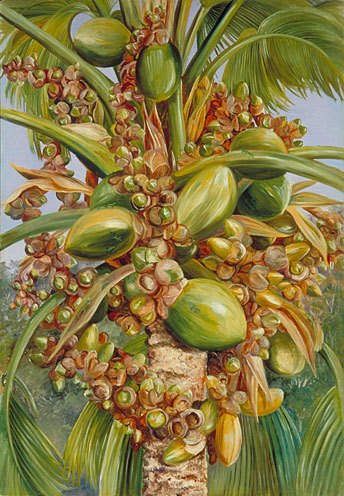

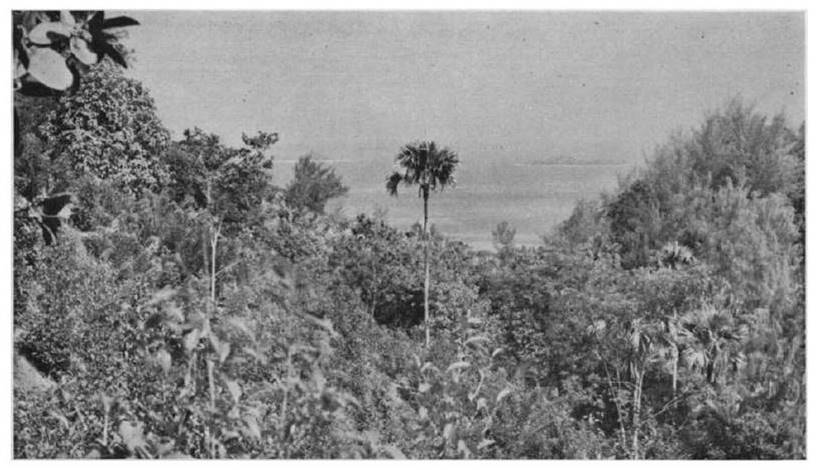

The sooglossid frogs favour undisturbed areas with good plant cover and a permanent water source. Sooglossus sechellensis on Mahé and the Praslin sooglossid also utilise dense areas of bracken fern. With risk of fire and continuing development, these habitats are at risk of destruction, leaving fewer suitable areas of habitat for the sooglossids. Habitat protection therefore needs to be addressed urgently to safeguard these frogs but the Praslin sooglossid fortunately appears to have a healthy population in the coco de mer forest of the Vallée de Mai, providing yet another reason for continued protection of this biodiversity-rich site.